The Indo-Pacific: A Pause in the Game

The State of Play

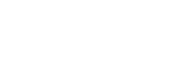

As a Covid-wounded global community steps gingerly into 2021, a year ‘trumpeting’ a change of guard in the US, the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and an ongoing military stand-off between India and China, it is a good time as any to take stock of the state of play in the vast volatile waters of the Indo-Pacific.

Part geography, part strategy, part connectivity, part battle-space, the Indo-Pacific (IP) is now clearly the jackpot in the planet’s geo-strategic sweepstakes, and the center-stage on which the new edition of the ‘great game’ is being enacted. It is also the theatre in which the Middle Kingdom has chosen to challenge both the US, as well as the Asian status-quo, in its pursuit of the Chinese Dream, and of great-power status.

The nascent concept of the IP, barely a decade old in 2017, received a fillip and gained broad usage and considerable traction during the Trump years, as the mercurial and unpredictable President called-out Beijing across the board, and denoted it as a ‘major adversary’ in no uncertain terms. This was accompanied by a flurry of actions and initiatives on the ground – trade wars, Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) withdrawal, renaming Pacific Command (PACOM), a new Tibet policy, and revitalizing the QUAD, amongst many others. In similar fashion, the Trump administration also ratcheted up the pressure on Iran, whilst facilitating rapprochement between Arabs and the Israelis.

It would not be inaccurate to state that the waters of the entire IP region, both to the east and west of India, were vigorously churned during the last four years. Picking up the Chinese gauntlet, President Trump ruffled the waters of both the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), and forced all players, including Beijing and New Delhi, to recalibrate policies and plans honed in what many consider the ‘lost decade’ of strategic drift, which was the hallmark of the Obama years. The fall-out certainly served to focus the spotlight on an assertive, often brazen China, and made it the geopolitical and geo-economic epicenter for all other players, including the EU and Russia. Moscow, of course, for reasons quite apparent, has aligned itself with Xi Jinping’s China, whilst the EU is ambivalent and quite willing to engage economically with the Communist giant.

The Covid pandemic has further underscored the scepter of an aggressive People’s Republic looming large over the Orient, to hark back to a term defining the region in the heyday of Empire. Further, the events of the last four years have also impacted negatively on China’s soft power and trustworthiness, already severely eroded, as the so-called beneficiaries of Beijing’s largesse became cognizant of the debt traps and loss of sovereignty inherent in its Yuan diplomacy and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The net result of the actions of the Trump Administration, and of China’s own miscalculations on multiple fronts, saw many nations, including India, more willing to move away from policies of accommodating Chinese power, and more inclined to standing up diplomatically and militarily to the Dragon in diverse matters across the security and economic spectrums. To the many nations being bullied and pressurized, appeasing China no longer appeared to be the only option. This was particularly evident in the year gone by, as witnessed by the responses and actions of India, Japan, Australia, Taiwan and ASEAN members, both individually and collectively.

India, in particular, forged a decisive path, particularly after the Chinese incursions in Ladakh. Building on itsearlier pro-activeness witnessed in the Doklam crisis, and its firm stance on the BRI, New Delhi jettisoned its reservations about the QUAD, cementing its ties with the US, Japan and Australia; signing foundational military logistics and communication agreements with Tokyo, Washington and Canberra; and inviting the Australian Navy into the fold of Malabar. Whilst QUAD is nowhere near a military alliance, the inherent strategic signaling to Beijing certainly adds to deterrence. On its northern borders, India was also demonstrably seen to aggressively resist Chinese salami-slicing, and upping the costs for any adventurism on the part of the PLA by matching troop deployments and preemptive actions.

Australia too, reversed years of caution due to its trade dependencies, and Premier Morrison pushed backhard against China’s perfidy in local affairs, blatant threats and economic blackmail, with considerable support from outraged public opinion. Premier Abe, whilst exploring options, stood firm in the face of grave Chinese and North Korean provocation in the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan, as did the Taiwanese and the ROK. ASEAN powers, like Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines and even Malaysia, whilst wary of strategic currents undermining ASEAN centrality, did protest and take cautious action against Chinese activities in the contested waters of the South China Sea.

Put together, all these developments did serve to check the pace of Chinese claims and seizures beyond what had been fairly easily accomplished by Beijing in the Obama Era. China still resorted to armed incursions and action at sea and on land borders, such asin Bhutan, but more to probe and test the waters, rather than through major acts of changing geographies, and substantially altering the military equation in the Western Pacific, such as witnessed in the reclamation and weaponization of reefs and islands in the Paracel’s and Spratlys. Moreover, it refrained from imposition of Air Defence Identification Zones (ADIZs), kept reasonably clear of the Scarborough Shoal in the vicinity of thePhilippines, and played around in the proximity of the Senkaku islands and the Taiwan Straits but without major military action.

Nevertheless, Chinese warships, submarines, fishing trawlers and intelligence survey ships continue to be deployed in the Indian Ocean, both in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. Beginning with the first anti- piracy deployment in 2008, the Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has been continuously present in the IOR, and engaged in showing the flag around the littoral and the islands of the ocean. With exclusive facilities at a number of ports including Karachi and Djibouti, the PLAN is better supported logistically than ever before. However, its lines of communication are stretched, and access in and out of the IOR severely constricted. Unlike in the China Seas, the PLAN is highly vulnerable West of Malacca, and its combat effectiveness in the Indian Ocean is questionable.

To the west of India, as in the Pacific, Trump was equally disruptive in upending the scenario prevalent at the start of his term, and withdrew from the Iranian nuclear deal or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. Tehran was put under sanctions, and the head of the Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard General Soleimani, was eliminated. Actions of US forces also brought about the defeat of the Islamic State, and the end of Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. The US Embassy was shifted from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and the Trump-brokered Abraham accords succeeded in upending Israel’s isolation in the Arab world.

The upshot of this particular churn is that Iran has drawn closer to China, and an informal axis of like-minded, US-opposed powers comprising Turkey, Iran, China, Pakistan and Russia is emergent and discernible. The Iran Russia naval exercise held earlier this month is indicative of this. This certainly has major ramifications for India.

The US stonewalled Islamabad almost entirely during the Trump Years, and removed most traces of Indo-Pak hyphenation. US-Pakistan relations reached their nadir in this period. In a major blow to Beijing’s, and indeed Pakistan’s plans, the US also entered into defence arrangements with the Maldives in 2019, limiting the activities of the nexus. Clearly, this was driven by the strategy of enabling India to be capable of counterweight to China, as indeed starkly recorded in the recently leaked Indo-Pacific Security Framework.

The dynamics of the Russia-US relationship have also distinctly impacted the geopolitics of the IP. For reasons linked to investments by many large US corporations in China, and remnants of a Cold War hangover, the American establishment has been inclined to make more of a bogey of Russia than of the potentially far greater threat emanating from the PRC. President Trump was a departure from this normal, and saw merit in a détente with Moscow to be able to focus on the Dragon. Vested interests within the permanent US establishment, along with Russian miscalculations in Europe and West Asia, resulting from an understandable deep-rooted animosity towards the apparent victors of the Cold War, prevented any improvement in US-Russia ties and trust. The Bear now finds itself playing an uncomfortable understudy to the Dragon globally and certainly in the IP. Realising Putin’s dilemma, both India and Japan are making efforts to wean Moscow away from Beijing, and also act as a check on China.

The French have certainly upped their profile in the IP over the last decade, and have developed stronger assets and linkages to play a significant role in the overall geo-strategic balance in the region, especially off the West Coast of Africa, and the Gulf of Aden and the islands of the southern Indian Ocean. To a lesser degree, the EU and the UK have also made their presence felt in these sane waters.

Time- Out

This, then, is broadly the state of play. As we enter the Biden era, it is readily apparent that the new team in Washington is set to reverse many of the Trump-era policies in both domestic and international arenas, including US stance and nuance towards China, Russia, Iran and Israel, with major repercussions for West Asia, East Asia, and the Indo-Pacific as a whole. Concurrently, the global vaccine efforts may bring the pandemic under control towards the latter half of the year. Taken together, it is a ‘wait-and watch’ time for the world as the 2020 playbook, dominated by Trump and Covid-19, is majorly re-written.

This rescripting will doubtless further churn the already ruffled waters of IP. Major uncertainties run rife for all players, including the state of the pandemic, and not least in the nature and extent of economic recovery from the ravages of Covid-19. It would thus be fair to denote the first half of 2021 as a ‘pause in the game’, a strategic ‘time-out’, as it were, during which national capitals and strategic communities of the region will attempt to re-evaluate their positions.

What then are the prospects for the major players in the IP? What progress can we expect by way of a free, open, peaceful, rules-based, prosperous and inclusive Indo-Pacific? Will Biden walk the tough talk? What would be the likely reactions of the CCP to a US president, who is a familiar figure and far more predictable, and ‘reasonable’? Without a pugnacious US in the lead, will the regional powers be able to check a rampant China, or will Beijing shortly dominate the economic and security framework from Africa to Oceania? Will Xi Jinping’s grip on the CCP remain unchallenged? Will a blatantly repressive regime manage to contain the civic unrest and protests mushrooming on its periphery? In other words, will the churning, incipient in the pause, result in a storm, or will it subside into a noisy calm?

These questions reverberate across the Indo-Pacific, but the strategic horizons remain hazy for all stakeholders, and it is unlikely that the contours of the IP will crystallise in the near term, or be discernable to even the most astute observers at this point of time. It may, however, be possible to outline the broad options available to the major players when the game unfreezes and resumes.

Resumption of Play

In their centenary year, the leaders of the CCP will surely continue with the declarative narrative of China’s ‘manifest destiny’ to be the world’s leading great power by 2049, and the associated bombastic rhetoric. Infrastructure work will continue apace in the South China Sea (SCS), and within the waters enclosed by the nine-dash line. They will also persist with forays and incursions around Taiwan, the Philippines, and the Senkaku islands

It would also be quite logical to assume, that with a likely more predictable and less combative US Administration, Beijing would be inclined to press home its advantages, in terms of a quicker post-Covid-19 economic recovery and a strong military position in the Western Pacific, to further its aggressive designs across the Indo Pacific. In the SCS in particular, it’s Anti-Access and Area Denial (A2AD) strategy has certainly borne fruit, and the balance of power has shifted in China’s favour, all manner of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) notwithstanding. It does appear to be an opportune moment for the Chinese to reclaim the momentum of dominance, which had been stymied over the last few years.

On the other hand, it is also a good time for Beijing to back off, using the likely softening of tone, and a notching-down of the present highly adversarial situation, after a few weeks of bluster by the incoming Biden administration. This would allow a face-saving means of re-focusing on the economy, and mitigating the almost universal and increasing ‘pushback’, most visible in the Quad, against the assertive military and economic policies of the Xi Jingping era. This would also help in halting a possible exodus of business ventures from China, as more nations adopt a policy of diversification in an attempt to lessen dependence on the manufacturing giant. Additionally, it would also allow the PRC leadership to concentrate on addressing the country’s many military and social vulnerabilities, before stepping out again to further its perceived notions of the Chinese Dream.

Moreover, whilst some analysts still see the possibility of a PLA onslaught in Taiwan, and indeed in the Himalayas, it is highly unlikely that the CCP leadership can afford the very real prospect of embarrassing and potentially disastrous reversals, and significant human and material losses, to which such misadventures might expose them. Failure to achieve objectives and expectations of the masses would make a huge dent in the Party’s gung-ho narrative, and its credibility and popularity during a celebratory year. As it is, Beijing faces considerable opposition, both internal and external, to its high-handedness in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, and a renewed spotlight on Tibet. The regional Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) and the BRI canalso bloom and benefit Chinese interests only in untroubled environs, and this would add to the rationale for keeping the broad peace. In sum, it makes more sense for Beijing to step back a bit.

This may however be optimistic and wishful thinking. Historically, authoritarian regimes tend to overestimate their strengths, and underestimate the opposition, especially of noisy democratic states. If the politburo of the CCP sees merit in backing the overtly aggressive slant associated with Xi Jinping, as well they might, storm clouds will quickly gather, despite the overarching desire of the Biden Administration and the EU to seek the good old days of mutual economic benefit. In this case we will witness more saber-rattling and brinkmanship in select areas.

On balance, however, it is unlikely that the CCP politburo will proceed to whip up a storm in the waters of the Indo Pacific until it assesses US resolve. Its predatory instincts would likely be trumped by those of self-preservation, and the apex leadership would be more inclined to calm the turbulent two-ocean space, whilst maintaining aggressive commentary and disinformation. This would enable gauging the responses of the new czars of Washington, as well as consolidate territorial claims, whilst the region analyses the depth of US response to the challenger power, beyond the initial tough optics and brave words.

On the other side of the fence, the Biden Presidency is in young days yet, and it would be unwise for anyone to put a definitive stamp on its likely actions, especially in regard to China, a named and called-out adversary, which poses a clear and present danger to American interests. However, Biden’s general disposition and world- view is more than discernible in the early activity seen in Washington in 2021, and from the record of the Obama years. Suffice to say, US foreign policy will almost assuredly be more conciliatory and conventional than it was under the previous President.

The US is reeling under the twin weight of the pandemic and massive internal polarisation and discord. Pre-occupied by domestic concerns, and the seemingly unbridgeable ideological chasms in their polity, Americans are not well placed to take on a fight in the Indo-Pacific. Whilst this may be of strategic utility to the Chinese, Beijing is unlikely to avail of this rare opportunity, for reasons highlighted earlier. The US is likely cognizant of the CCP’s dilemmas, and would thus be happy enough to engage in a war of words and in optics, while being careful not to overstep US red-lines.

The US is likely to continue supporting the Quad/Quad plus Dialogues, and all its military alliances and commitments in the IP, but the warnings and signalling to Beijing will likely weaken, as US trade and fortunes get hyphenated once again to the Middle Kingdom’s enormous manufacturing expertise, undertaken in an authoritarian bubble, without the economic brakes applied by noisy democracies through media, courts, protests, regulators and labour activism.

Japan and Australia are now also likely to be interested in a lowering of tensions with Beijing. Japan faces increasing PLA/PLAN might in the East China Sea (ECS), as Chinese military force levels and capabilities have increased exponentially over the last decade. Whilst under US military protection, Tokyo may be somewhat concerned over the level of US commitment and engagement with the region; as well as the capability of US forces in the Pacific, in relation to the PLA’s technological and numerical enhancement. Australia, while attempting to diversify its exports and imports, is prey to enormous economic pressure from Beijing, and would be wary of continuing to stand up to China in the absence of any wavering of US support and guarantees. Both countries have signed up for RCEP, and are therefore more likely to engage China economically.

The same rationale would be applicable to most of the ASEAN member-states, with the added problems of proximity and yawning gaps in military capability vis-a-vis China. None of them would like to be caught in crossfire, or become subsidiary to larger security architectures and arrangements which would detract from their interests and centrality.

Of particular note in the game now underway would be Chinese moves in the Bay of Bengal states of Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Bangladesh. Connecting the waters of the Bay with the Chinese mainland through suitable deep-water ports feeding pipelines/ railways offers the Chinese the only real alternative to their Malacca Dilemma. Arctic routes and the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) are not really viable, given the quantities, the distances, and the weather, especially in conditions of conflict. The recent military takeover in Myanmar may bode well for Beijing’s plans, and Dacca remains vulnerable to economic support and enticements.

With the Saudi-Qatar issue resolved, West Asia will likely see fewer of the many internecine quarrels which have consumed it since the fall of the Ottomans, but this may be replaced by a hardening of the ethnic divide and possible conflict between the Turks and Persians, if you will, on one side, and the Arabs and the Jewish state making strange bedfellows on the other. However, it is too early in the game to call this sort of line-up as given. Much will depend on the machinations of external players, especially Russia, China and the US. The ability of the Arab block to eschew radicalism will also play a major part, as will the fate of Islamism in Turkey. Clearly, the most important factor in this sub-region of the IP will be Tehran’s attitudinal approach to the nuclear issue and its neighbours after the Americans re-enter the JCPOA, a course of action the new president strongly supports.

In the pause now underway, New Delhi’s China policy is likely to get more nuanced, in search of lowering tensions. The recent synchronized withdrawal of troops on the LAC certainly affords such a possibility. It does appear that the forthright Indian opposition to China’s more overt gambits will continue. However, New Delhi will likely factor-in Beijing’s reluctance to opt for military conflict on one hand, along with an expected relative weakening of diplomatic, material or moral support from the US on the other, especially in comparison to what was forthcoming in the Trump years. A dwindling US commitment may be exacerbated by the S-400/ Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) imbroglio, and an increased proclivity of disparate groups linked to the Democratic party in the US to comment on India’s internal affairs, waving the banner of human right concerns. Statements from Foggy Bottom are also already indicative of some re-hyphenation of India and Pakistan.

Befitting a democracy, and in keeping with the stereotype of the ‘argumentative’ nature of the Indian discourse, there are distinct camps of opinion in regard to Delhi’s long-term options. Many see the advantages and opportunity in a stronger alignment with the US to keep China at bay, and to avail of technological and economic potentialities.

There is, however, a significant element in the Indian strategic community which is distrustful of US intent and commitment, and has been cautioning against too close an American embrace. This group favors ‘strategic autonomy’ and ‘issue-based alignments’, along with continuing strong ties with Russia, France, Israel, Japan and Iran.

Cognizant of the present economic and military capability gap that exists between China and India, and mindful of the reducing differential between US and Chinese power in the IP, there is another school which advocates a more graded approach to Beijing’s many transgressions and irritants, seeking accommodation and compromise whenever possible.

Despite Doklam and Ladakh, a significant number on the left still believe India should continue to pursue strong ties with Beijing, for economic advantage and ‘Asian solidarity’! This faction is ideologically driven, and views the US with the utmost suspicion, with colonial and imperialist designs.

Though it may be too early to evaluate the likely direction of Indian foreign policies hereon, it would be within bounds of analytical reasoning to infer that much will depend on the actions of the CCP and the US during the present transitional pause. Indeed, the same could be said of the likely response all other major players in the IP region, as all stakeholders evaluate the US-China dynamic under Biden, and try and discern the rapidly changing strategic contours in West Asia.

A turn of events in Russia may also well surprise, though Putin’s grip on power appears firm despite protests and the Navalny episode. However, any tectonic shift in the Kremlin could impact on the IP through any reset of Moscow-Beijing ties. EU China economic ties may also impact the overall geopolitics of the region.

Deuce

The world, battered by Covid-19, is straining to realize some semblance of normalcy, a lessening of global anxieties and revival of economies. If Beijing were to show signs of being willing to conform to even some of the admittedly imperfect rules of the contemporary world order, it is more than possible that major powers will respond positively. In other words, irrespective of the state of play in 2020, the match could thus remain drawn. In geopolitical parlance, a balance of power may be achieved in the IP.

However, even if Beijing were to tone down, it would be likely tactical and temporary, unless there is a fundamental shift in Chinese ambitions, only realizable through a change of regime/ leadership. China’s territorial and economic aggressiveness would reassert, especially if there is increasing disarray in the US. Viable international engagement and leadership by the US is only possible if there is some semblance of domestic unity.

In the IP, there will be considerable temptation and advice to accept the reality of China’s rise and power, to live with and adjust to its economic and manufacturing dominance, in fact, to try and glean advantage from it. Though this may appear eminently rational, such an approach is fraught with danger when dealing with totalitarian militaristic states. Acceptance of Chinese transgressions through turning a Nelson’s eye, through deal-making, or worst, through appeasement will only serve to whet the Dragon’s appetite.

Despite much analysis, the goings-on in the upper echelons of the CCP remain “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” in similar fashion to this description of Russia by Churchill. Opposition within the party to Xi Jingping’s present interpretation of the Chinese Dream, as well as the always possible and sudden advent of social and economic fractures in brittle authoritarian states, make crystal-ball gazing a hazardous sport insofar as the Middle Kingdom is concerned. The Game could certainly be turned around by events out of the control of the Son of Heaven residing in the Forbidden Palace.

Furthermore, there is always the possibility that Chinese hubris or miscalculation could tip the scales, and cause an uncontrollable cloud burst. China’s recent gambit of allowing its Coast Guard to open fire on foreign vessels is one such example of rashness, which is also indicative of a poor understanding of the use of force at sea, and its cascading results.

In conclusion, it could be said that storm clouds will continue to darken the skies and waters of the IP in the foreseeable future. The resumption of play mid 2021 on wards will determine whether the clouds dissipate, and the blue-skies prevalent in the first decade of this millennium return to the region. At this point, the game is deuced, and unless the US pulls its act together, and the pandemic dissipates, the game will be ‘Advantage China’.

It would thus be in order for New Delhi to remain on even keel in respect of its relationship with Beijing, focussing on China’s capabilities, not intentions. In this regard no amount of advocacy for building conventional kinetic military capability is ever too much. Deterrence and dissuasion are best achieved by capacity building and keeping powder dry, whilst of course pursuing diplomacy and alignments. It would also be wise to focus on military brass-tacks, instead of being led astray by the more esoteric realms of ‘hybrid warfare’, and of the ambiguous and amorphous threads of that over-arching term ‘national security’, which often detracts and dilutes from ground-level realities. This will call for realism, and adequate funding of the requisite military capabilities and hard power.

Written by and published originally in www.vifindia.org and being reproduced with due permission from Vivekananda International Foundation, Delhi duly acknowledging their copy rights.