Bookending the Indian Ocean: China, RCEP and the Mauritius FTA

Trade deals and major investment decisions are never taken solely on the basis of economic grounds. There is an element of political preference running through the choice of any state for increasing and/or decreasing trade relationships. States carefully weigh in the costs and benefits of constructing economic relationships and decide whether to pursue a particular course of a policy action or not. In contemporary international affairs, examples of such behaviour are aplenty. Around 2014-15, United States’ (US’) decisions to enter into Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) were clearly driven by the economic logic as much as by the political objectives of strengthening alliances in Europe and in Asia. In 2014, American ambassador to European Union (EU), Anthony Gardner had said that “there are critical geostrategic reasons to get this deal done. Every day since my arrival, I am reminded of the global context of why we are negotiating TTIP”.[i] Moreover, he was explicit in pointing out the challenges in the Middle East and Russia and said that in this context the TTIP will “help solidify further the transatlantic alliance, to provide an economic equivalent to NATO, and to set the rules of world trade before others do it for us”.[ii] A similar point was made by Michael Froman, US Trade Representative, in the context of TPP when he said that the “TPP is a critical part of our overall Asian architecture. It is perhaps the most concrete manifestation of the President’s rebalancing strategy towards Asia”.[iii] He had further added that “TPP’s significance is not just economic, it’s strategic – as a means of embedding the US in the region, creating habits of cooperation with key partners, and forming a foundation for collaboration on a wide range of broader issues”.[iv]

As economic tools are often deployed to achieve desired political outcomes, a persuasive case can be made to pay closer attention to the phenomenon of geo-economics and its role in shaping international relations. Geo-economics is defined as “the use of economic instruments to promote and defend national interests, and to produce beneficial geopolitical results; and the effects of other nations’ economic actions on a country’s geopolitical goals”.[v] This definition frames geo-economics as a method of analysis as well as an instrument of statecraft. It is argued that China is the world’s leading practitioner of geo-economics. Never before in world history, has any single government controlled so much wealth.[vi] And as China’s affluence and material power went up, its ability to deploy geo-economic tools to achieve political objectives also grew considerably. In the past, China has meted out economic penalties of some form to countries that host Dalai Lama.[vii] China had also halted the supply of rare earths minerals to Japan in 2010 following a political row.[viii] The latest instances of China’s trade deals, the operationalisation of its Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Mauritius and signing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), are likely to increase China’s ability to exercise geo-economic tools.

China-Mauritius Free Trade Agreement

Mauritius is the first African country with whom China has signed an FTA.[ix] This agreement is significant not only for China’s trade relations with Africa but also for its implications on the geopolitics of the Indian Ocean. Traditionally, Mauritius has been considered as India’s key Indian Ocean partner and therefore, the FTA and consequently the growing Chinese role have implications for India’s influence in the region. Let’s look at these factors more carefully.

It is well-known that China is the largest trading partner of Africa and in 2019, bilateral trade between China and Africa stood at $ 192 billion. Angola, South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and the Republic of Congo are some of the major trading partners of China in Africa.[x] It is expected that China’s FTA with Mauritius, which was signed in October 2019 and came into effect in January 2021, is likely to prove crucial in further opening African markets for China.[xi] For Mauritius, China is its largest trading partner and the trade balance is heavily skewed in favour of the latter. In the Mauritian import basket, China tops the list with a 16.7% share and is closely followed by India with 13. 9% share in overall imports.[xii]

Chinese and Mauritian economies are not complementary to each other. It was noted that “what Mauritius excels at exporting, China does it too, and does it better and cheaper. In fact, Mauritius’ largest export, textiles, are in direct competition with China”.[xiii] As per the provisions in the FTA, Mauritius will get, “duty-free access on the Chinese market on 7,504 tariff lines. Tariffs on an additional 723 tariff lines will be phased out over a 5 to 7-year period starting 1st January 2021. In addition, a Tariff Rate Quota for 50,000 tonnes of sugar will be implemented on a progressive basis over a period of 8 years with an initial quantity of 15,000 tonnes”.[xiv] However, in this context, it necessary to consider whether Mauritius will get any tangible benefits out of this trade deal. Alex Vines, head of the Africa Programme at Chatham House believes that through the FTA “Chinese will significantly benefit”.[xv] In fact, “there is a massive trade imbalance between Mauritius and China, in favour of China. We’ll have to see how much Mauritius will benefit”.[xvi]

Mauritius, on its part, hopes to attract greater Chinese investment through the FTA. For Chinese firms, Mauritius can act as a gateway to Africa. Meanwhile, African countries are building a single market through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into effect last month. It is likely to create a single market of 1.2 billion people with a combined market worth $ 3 trillion.[xvii] China’s role as Africa’s foremost trading partner and easier access to the market facilitated by FTA with Mauritius is likely to further boost China’s trade ties with Africa.

China’s choice of Mauritius for signing FTA is also significant as the tiny Indian Ocean country does not produce anything significant, except sugar, but is located in a geo-strategically valuable location. Mauritius, a country with a population of 1.3 million, lies at the crossroad of Asia, Africa and the West Asia. There are Mauritian citizens of Chinese origin who make up about 2-3% of the population. Mauritius is known as a hub of financial services, an attractive tourist destination and is well-known as a tax haven.[xviii] Based on this, it can be inferred that, for China, reasons for signing FTA are not necessarily found in the trading potential of this economically rich and politically stable country but in other factors like its geographic location.

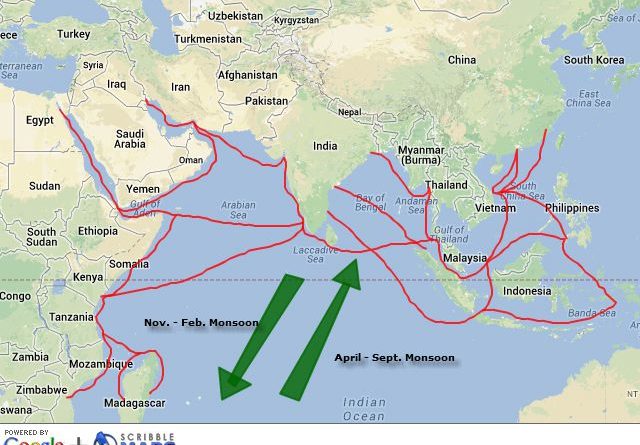

Over the years, China has built strong ties with the neighbours of Mauritius such as Seychelles and Madagascar to the south and Sri Lanka to the north. China is also an observer in the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), a group of five island countries in the South-West Indian Ocean including Mauritius.[xix] For China’s international trade, the maritime space around Mauritius is critical as a foothold in Mauritius could facilitate monitoring of shipping lanes that crisscross the Indian Ocean. China had opened a military base in Djibouti in 2017 and the Chinese Navy pays regular visits to the littoral and island countries of the Indian Ocean like Pakistan to conduct defence diplomacy.[xx] Therefore, China’s strategic interests in the Indian Ocean and geo-economic realities are coming together in the maritime region around Mauritius.

China in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)

RCEP was signed in November 2020 and is expected to shape the economic future of the Indo-Pacific region in the coming decades. China is a key member and the largest economy in the RCEP that brings 15 major economies of the Indo-Pacific region together.[xxi] China has taken an active interest in pushing for the RCEP and includes countries that are friendly (like Cambodia) and not-so-friendly (like Australia, Vietnam and Japan) towards Beijing.[xxii] It is estimated that RCEP, which excludes the US, is the “largest trading bloc globally, covering a market of 2.2 billion people and $26.2 trillion of global output. This accounts for about 30% of the population worldwide, as well as the global economy”.[xxiii] It is larger than the European Union (EU). RCEP has created the basis for deeper economic relationships in the Indo-Pacific region. It has been considered a diplomatic as well as geopolitical success for Beijing.[xxiv] The absence of India and the US has left the trading bloc open to the Chinese leadership and seen in the framework of geo-economics is likely to have implications for the geostrategic trajectory of the Indo-Pacific region.

Geopolitical Impact

Taken together, these two trading arrangements (RCEP and China-Mauritius FTA) are bookending the Indian Ocean and lay the foundations for the further expansion of Chinese influence. RCEP covers the Eastern Indian Ocean and, AfCFTA covers the Western Indian Ocean. China enjoys robust trading relationships with Africa as well as RCEP countries including those in Southeast Asia and consequently, is likely to loom large over the trading dynamics of the Indian Ocean. China is already a major economic partner for West Asian countries as well as Pakistan. In 2019, West Asia accounted for 44% of Chinese oil basket and Saudi Arabia was the largest supplier of oil with 16% share in the Chinese oil imports.[xxv] Recently, China signed long-term energy and strategic deal with Iran.[xxvi] Therefore, through these relationships and trading arrangements, China is likely to loom larger over the economic, energy and infrastructure structure of the entire Indian Ocean Rim, from South Africa to Australia via West, South and Southeast Asia. Such a presence and ease of access coupled with the formidable economic muscle is likely to further enhance its geopolitical weight. For India, it has serious strategic and geo-economic implications.So far, India has not joined RCEP and is the third largest trading partner of Africa with a bilateral trade hovering around $ 67 billion, which is about one-third of Sino-African trade.[xxvii] The current period of sluggish economic growth at home possibly influenced India’s strategic choices. Therefore, India needs to take corrective steps which will include solidifying economic and strategic ties with the Indian Ocean Rim including the Vanilla Island nations of the Southwest Indian Ocean. In this context, the recent visit to Mauritius by India’s External Affairs Minister (EAM) S Jaishankar assumes significance.

From February 20-23, 2021, EAM Jaishankar paid a visit to the Maldives and Mauritius. During the visit, India and Mauritius signed a slew of agreements to deepen their economic and strategic relationship. Mauritius became the first country with whom India signed the Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and Partnership Agreement (CECPA). The agreement is expected to “provide a timely boost for the revival of our post-COVID economies and also enable Indian investors to use Mauritius as a launch-pad for business expansion into continental Africa”.[xxviii] It will further solidify Mauritius’ role as a ‘hub of Africa’.[xxix] The agreement “provides preferential access to Mauritius for the bulk of the trade and also for many aspirational items for the future into the Indian market of over a billion people”.[xxx] Through CECPA, products like “frozen fish, specialty sugar, biscuits, fresh fruits, juices, mineral water, soaps, bags, medical and surgical equipment, and apparel” are likely to enjoy the easier access into the Indian market.[xxxi] About 76% of Mauritius’ GDP is contributed by the services sector and the “bilingual prowess” of Mauritius is likely to help India’s IT companies to enter into French-speaking parts of Africa.[xxxii]

In this visit, India also extended the $ 100 million lines of credit for the purchase of defence equipment.[xxxiii] For India, the stakes in Mauritius are very high. Historically, Mauritius is a close partner of India and the growing footprint of China in this country is a worrying development. India is developing military infrastructure on Agalega Island and is hoping to acquire a firm foothold in the Southwest Indian Ocean. India’s growing ties with France, the US as well as with other Southwest Indian Ocean countries like Seychelles and Madagascar are likely to have a role to play in this regard. Revival of domestic economic growth is also a difficult but necessary course of action for India to tackle the Chinese challenge. Growing economy and deepening strategic relationships tend to offer a series of interesting choices that would benefit India to preserve and expand its influence in the region.

Going forward, it will be interesting to see how the geo-economic weight of India and China shapes the strategic competition in the Indian Ocean.

Endnotes

[i] Daniela Vincenti, “US Ambassador: Beyond growth, TTIP must happen for geostrategic reasons”, Euractive, July 14, 2024, available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/trade-society/interview/us-ambassador-beyond-growth-ttip-must-happen-for-geostrategic-reasons/ (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “Remarks by Ambassador Michael Froman at the CSIS Asian Architecture Conference”, September 22, 2015, available at: https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/speechestranscripts/2015/september/remarks-ambassador-michael (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[iv] Ibid

[v] Robert D. Blackwill and Jennifer M. Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 2016, pp. 19-22

[vi] Ibid, pp. 93-94

[vii] Ibid, pp. 129-130

[viii] Keith Bradsher, “Amid Tension, China Blocks Vital Exports to Japan”, The New York Times, September 22, 2010, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/23/business/global/23rare.html (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[ix]TRT World, “China-Mauritius FTA goes into effect. But who benefits?”, January 4, 2021, available at: https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/china-mauritius-fta-goes-into-effect-but-who-benefits-42954 (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[x]China-Africa Research Initiative, “Data: China-Africa Trade”, 2021, available at: http://www.sais-cari.org/data-china-africa-trade#:~:text=The%20value%20of%20China%2DAfrica,by%20South%20Africa%20and%20Egypt. (Accessed on march 18, 2021)

[xi]Rosie Wigmore, Will Africa’s First Free Trade Agreement With China Actually Help Africa?”,The China Africa Project, October 2, 2020,available at: https://chinaafricaproject.com/analysis/will-africas-first-free-trade-agreement-with-china-actually-help-africa/(Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xii]Mauritius Trade Easy, “Mauritius Trade profile”, October, 2020, available at: http://www.mauritiustrade.mu/en/trading-with-mauritius/mauritius-trade-profile (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xiii] Chris Devonshire-Ellis, “Why The China Mauritius Free Trade Agreement Opens Up The African Belt And Road”, Silk Road Briefing, January 5, 2021, available at: https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2021/01/05/why-the-china-mauritius-free-trade-agreement-opens-up-the-african-belt-and-road/ (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xiv]Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade (Mauritius), “Communique”, December 28, 2020, available at: https://foreign.govmu.org/Communique/Mauritius-China%20Free%20Trade%20Agreement%20will%20enter%20into%20force%20on%2001%20January%202021.pdf (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xv]TRT World, “China-Mauritius FTA goes into effect. But who benefits?”, January 4, 2021, available at: https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/china-mauritius-fta-goes-into-effect-but-who-benefits-42954 (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Lauren Johnston and Marc Lanteigne, “Here’s why China’s trade deal with Mauritius matters”, World Economic Forum, February 15, 2021, available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/02/why-china-mauritius-trade-deal-matters/#:~:text=The%20agreement%20unites%20an%20estimated,China%20and%20an%20African%20state. (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xviii]Abdi Latif Dahir, “How an idyllic African island became a tax haven for some of the world’s biggest corporations”, Quartz Africa, July 23, 2019, available at: https://qz.com/africa/1673027/how-did-mauritius-become-a-global-tax-haven/ (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xix]Indrani Bagchi, “India accepted as observer in Indian Ocean Commission”, The Times of India, March 6, 2020, available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-accepted-as-observer-in-indian-ocean-commision/articleshow/74517245.cms (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xx] Sankalp Gurjar, “Geopolitics of the Western Indian Ocean: Unravelling China’s Multi-Dimensional Presence”, Strategic Analysis, 43 (5), 2019, pp. 385 – 401

[xxi] Joshua Kurlantzik, The RCEP Signing and its Implications”, Council on Foreign Relations, November 16, 2020, available at: https://www.cfr.org/blog/rcep-signing-and-its-implications (accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xxii] Ibid

[xxiii] Yen Nee Lee, “‘A coup for China’: Analysts react to the world’s largest trade deal that excludes the U.S.”, CNBC, November 15, 2020, available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/11/16/rcep-15-asia-pacific-countries-including-china-sign-worlds-largest-trade-deal.html (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xxiv] Ibid

[xxv]US Energy Information Administration, “China”, September 30, 2020, available at: https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/CHN (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xxvi] ANI, “China, Iran enters $400 billion strategic partnership deal”, Livemint, July 15, 2020, available at: https://www.livemint.com/news/world/china-iran-enters-400-billion-strategic-partnership-deal-11594808074652.html (Accessed on March 18, 2020)

[xxvii]Ministry of External Affairs, “Speech by MOS at the 15th CII-EXIM Bank India-Africa Project Partnership Conclave” September 24, 2020, available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/33052/Speech_by_MOS_at_the_15th_CIIEXIM_Bank_IndiaAfrica_Project_Partnership_Conclave (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xxviii]Ministry of External Affairs, “Press Statement by External Affairs Minister during Official Visit to Mauritius”, February 22, 2021, available at: https://mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/33559/Press_Statament_by_External_Affairs_Minister_during_Official_Visit_to_Mauritius (Accessed on March 18, 2021)

[xxix] Ibid

[xxx] Ibid

[xxxi] Ibid

[xxxii] Ibid

[xxxiii] Ibid

Written by Dr. Sankalp Gurjar, Research Fellow, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi and published originally in www.icwa.in and being reproduced with due permission from Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi duly acknowledging their copy rights.